Introduction

The use of vaccines has transformed public health and many of the diseases that were previously responsible for the majority of childhood deaths have largely disappeared including Diphtheria, Measles, Pertussis, and Polio [1]. Vaccines are biological products that exploit the ability of the highly evolved mammalian immune system to respond to and remember encounters with pathogens. To induce protective immunity, the vaccine must contain pathogen-derived antigens. Vaccines are generally classified as live(-attenuated) and non-live vaccines depending on the nature of the antigens. Live-attenuated vaccines contain replicating strains of the relevant pathogen while non-live vaccines contain non-replicating pathogens or components of the pathogen. Vaccines containing components of a pathogen are known as subunit vaccines encompassing protein vaccines, polysaccharide vaccines, or conjugate vaccines. In addition to the traditional live and non-live vaccines, other types of vaccines have been developed for example nucleic acid-based RNA and DNA vaccines, viral vectors vaccines, and virus-like particles [2]. In most cases, live vaccines elicit a wider range of immunologic responses activating both humoral (B cells) and cellular (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) reactions than non-live vaccines and therefore also have significantly higher immunogenicity. Often, a single vaccine administration is sufficient to induce long-term protection [3]. Vaccines have not only transformed public but also veterinary health and are widely accepted as a cost-effective and sustainable immunization method for companion animals and livestock to efficiently prevent the transmission of zoonotic diseases [4]. *Campylobacter is one of the most important foodborne pathogens in Europe and the US, and the causative agent of campylobacteriosis. The disease manifests itself through mild to severe inflammatory diarrhea and can result in chronic implications such as reactive arthritis or Guillain-Barré-Syndrome. The main transmission occurs through the consumption of contaminated poultry meat which causes about 60 – 80% of global campylobacteriosis cases. Frequently, isolated Campylobacter from human infections showed resistance to various antibiotics. There are at present no vaccines approved by any global governing authority to prevent Campylobacter infections. Thus, vaccines represent a major unmet medical and industrial need to reduce the use of antibiotics, prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance, and raise food security [5] [6]. Zurich University of Applied Science and Malcisbo AG are currently developing an orally administered, live-attenuated vaccine against Campylobacter infections for broiler chickens. The high variability of Campylobacter jejuni (main Campylobacter gastroenteritis-causing member) with more than 60 serotypes makes vaccine generation against all serotypes a challenging endeavor [7]. Using Malcisbo’s glycoengineering platform technology a vaccine candidate covering all serotypes was established. The highly conserved protein-bound N-glycans of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are recombinantly expressed on the outer membrane of an attenuated Salmonella strain. First experiments using the glycoengineered vaccine against Campylobacter in chicken showed a reduction of Campylobacter jejuni in the chicken feces, suggesting a good efficacy of the vaccine candidate [8].

Process development and optimization

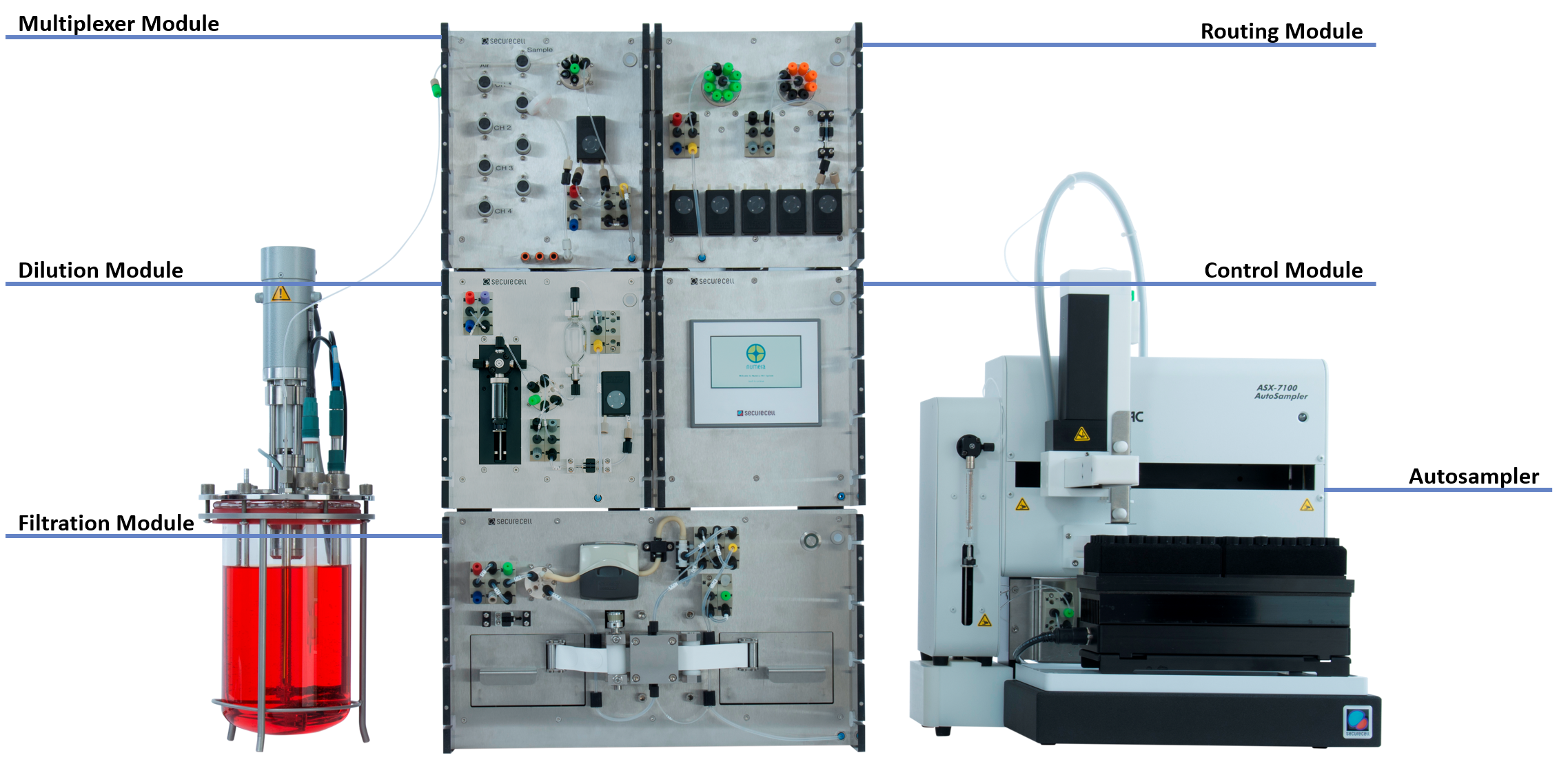

Over the last decade, cost control in biopharmaceutical manufacturing has become more relevant as margins, especially for vaccines compared to other biopharmaceutical products, are low. It is important to decide early in the development process how the product will be manufactured at a commercial scale. Changes later on such as new manufacturing equipment or raw material components will typically trigger new regulatory requirements, including clinical trials and thus additional costs [9]. To make an early decision on the process details i.e., optimal process conditions for the manufacturing of the Campylobacter vaccine candidate, the substrate concentration of critical growth medium components was altered marking different process phases during continuous culture and the influence on the antigen expression (AE) and cell size distribution was evaluated. To be able to track and reliably measure the surface AE and cell size distribution of the Salmonella culture with flow cytometry, liquid samples were taken in regular intervals for 245 h from the bioreactor and were analyzed. Securecell AG’s modular sampling system Numera® was used to complement manual sampling outside working hours by automatically drawing and storing samples in a cooled environment, making samples readily available for flow cytometric analysis. Numera® can be flexibly configured to allow sampling of up to 16 bioreactors or downstream devices in parallel, seamless in-built sample processing, and sample transfer to a sample storage unit or 3rd party analyzers (Figure 1). Compared to other sampling systems, Numera® allows for sampling of small sample volumes at a high frequency, reliable sample processing with a precise dilution (error ≤ 2% SD) and unique tape-filtration technology, cooled sample storage, and well-established integration with multiple cell and biochemical analyzers and HPLC systems.

Figure 1: Image of the Numera® automated sampling system. The Multiplexer Module forms the interface to the bioreactors. After optional sample processing by the Dilution or Filtration Module, the Routing Module directs the sample either to the autosampler for sample storage and off-line analysis or directly to connected 3rd party analyzers.

Figure 1: Image of the Numera® automated sampling system. The Multiplexer Module forms the interface to the bioreactors. After optional sample processing by the Dilution or Filtration Module, the Routing Module directs the sample either to the autosampler for sample storage and off-line analysis or directly to connected 3rd party analyzers.

Material and Methods

All experiments described were performed in a bioprocessing laboratory with a fully integrated IoT infrastructure (i2BPLab) at Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW), Wädenswil.

Cultivation conditions

The total process duration was 245 h including a 6 h preparation phase for a sterility check and media conditioning time. The continuous fermentation was performed in a 1.5 L Minifors 2 bioreactor (Infors HT) equipped with a pH, a dissolved oxygen (DO), and a Dencytee optical density sensor (Hamilton AG). Additionally, the reactor was equipped with a feed tube and two dip tubes. One dip tube was connected to an external peristatic pump to set the culture volume during the continuous phase (Fout). The second dip tube was split by a Y-connector and connected to Super Safe Samples (Infors HT), for manual sampling, and directly to the Numera® Multiplexer Module, for automated sample drawing. The reactor was supplied with air (1.5 L min-1) and O2 to control dissolved O2 around minimally 25 %. The temperature and stirrer setpoints were set to 37 °C and 1200 rpm, respectively. The pH was controlled at 7.2 by the addition of 25 % NH4+ and 8.5 % H3PO4.

Set-up automated sampling

The reactor system and the Numera® system were connected to and controlled by the software Lucullus® (Securecell AG). In Lucullus®, the sampling events were planned and, in the case of automated Numera® sampling, triggered during the process execution phase. From the samples, the surface AE level, the cell size distribution of the population, and the optical density at wavelength 600 nm (OD600) were determined. Additionally, for the manually drawn samples only, the cell dry weight (CDW) and the substrate concentration in the culture medium were measured. Other process-related parameters were measured in-line with the respective probes. Sampling intervals ranged from 1 – 6 h depending on the process phase.

Off-line sample analysis

CDW was measured by pelleting 2 mL of culture broth in a pre-weighed tube, discarding the supernatant, and drying the pellet at 105 °C for 48 h. For the estimation of the AE and cell size, the cells were stained with a fluorescent stain and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results and Discussion

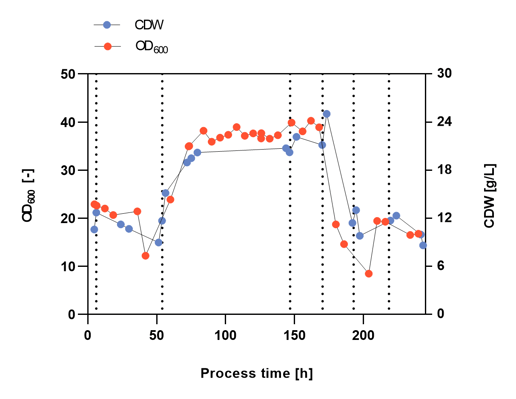

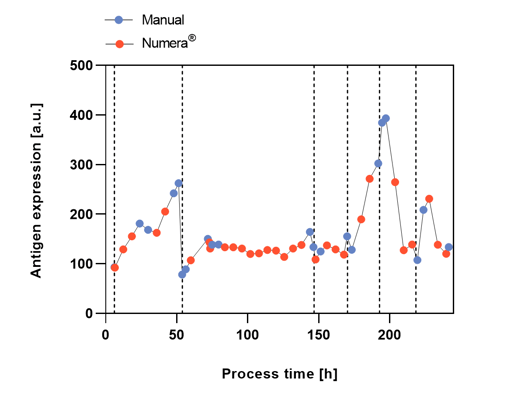

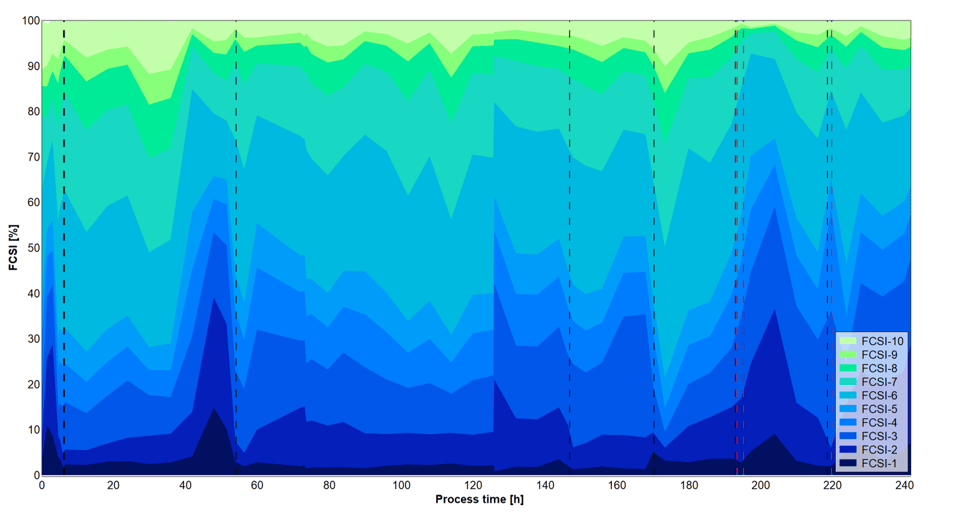

To explore optimal process conditions for the manufacturing of the vaccine candidate, the glycerol, tryptone, and yeast extract ratio in the growth medium was altered marking different process phases indicated by vertical dashed lines during the continuous culture (Figure 2-4). The aim of Malcisbo’s scientists was on the one hand process development and optimization (i.e., cell density) for upcoming industrial Campylobacter vaccine production, and on the other hand vaccine quality optimization (i.e., maximization of AE and cell size). Larger cells have a larger surface area and can thus express more of the antigen.

Figure 3: Antigen expression after manual or automated Numera® sampling over the six different process phases indicated by vertical dashed lines with varying substrate concentrations.

Figure 3: Antigen expression after manual or automated Numera® sampling over the six different process phases indicated by vertical dashed lines with varying substrate concentrations.

The cell densities over the complete process were measured after manual sampling and heating (CDW) or after automated sampling with the Numera® sampling system (OD600) (Figure 2). The cell density varied considerably in the different process phases most likely due to the different substrate concentrations. During phase 1, an unintended washout of the cells occurred from which the culture recovered. Both manual and Numera® automated cell density measurements showed a similar growth curve over the complete process. The cell density peaked at the start of phase 4. The manual and Numera® samples were also analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the surface AE (Figure 3) and relative cell size distribution of the population (Figure 4) over time. Also, the level of AE altered considerably in the different process phases. The increase of AE during process phase 4 was most pronounced, followed by phase 1. Similarly, the relative cell size distribution (FSCI-1 – FSCI-10) changed over process time. The relative number of big cells (> FSCI-6) was highest in mid-phase 4, followed by mid-phase 1.

Figure 4: Cell size distribution measured after automated Numera® sampling over the six different process phases indicated by vertical dashed lines with varying substrate concentrations. FSCI-1: very small cells. FSCI-10: very large cells.

Figure 4: Cell size distribution measured after automated Numera® sampling over the six different process phases indicated by vertical dashed lines with varying substrate concentrations. FSCI-1: very small cells. FSCI-10: very large cells.

Conclusion

Understanding how the cell density, the antigen presentation, and the relative cell size distribution are influenced by the process conditions is crucial. From a supplier perspective, Numera® successfully complemented manual sampling. An unattended Numera® sampling run between 80 h and 145 h process time delivered consistent results for OD, AE, and cell size. This exemplarily demonstrated the reliability of the Numera® system for high-frequency sampling during non-office hours and storage of the samples for later (flow cytometric) analysis. From a scientific perspective, these preliminary and exploratory experiments showed that substrate concentration for AE and cell size seemed to be optimal during phases 1 and 4 as in these phases AE and the relative number of big cells (> FSCI-6) peaked. However, the highest cell densities were reached during phase 2. This observation might be explained by the fact that after the washout, the cells invested energy and resources in proliferation instead of surface antigen expression. As the influence of the washout cannot be fully accounted for, the results have to be verified in subsequent experiments.

Key Results

-

Highly frequent and automated bioreactor sampling and sample storage with Numera®

-

Reliable sampling during non-office hours

-

Good accordance of off-line and on-line analytical results

-

Combination of Numera® and Lucullus® as integrated PAT solutions

-

Complete automation of sample-based analytics

References

-

World Health Organization. Global vaccine action plan 2011–2020. WHO https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/ (2013).

-

Pollard, A. J. & Bijker, E. M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 83–100 (2021).

-

Kollaritsch, H. & Rendi-Wagner, P. 9 - Principles of Immunization. in Travel Medicine (Third Edition) (eds. Keystone, J. S., Freedman, D. O., Kozarsky, P. E., Connor, B. A. & Nothdurft, H. D.) 67–76 (Elsevier, 2013). doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-1076-8.00009-0.

-

Jorge, S. & Dellagostin, O. A. The development of veterinary vaccines: a review of traditional methods and modern biotechnology approaches. Biotechnology Research and Innovation 1, 6–13 (2017).

-

Igwaran, A. & Okoh, A. I. Human campylobacteriosis: A public health concern of global importance. Heliyon 5, (2019).

-

Facciolà, A. et al. Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention. J Prev Med Hyg 58, E79–E92 (2017).

-

Munroe, D. L., Prescott, J. F. & Penner, J. L. Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli serotypes isolated from chickens, cattle, and pigs. J Clin Microbiol 18, 877–881 (1983).

-

Plotkin, S., Robinson, J. M., Cunningham, G., Iqbal, R. & Larsen, S. The complexity and cost of vaccine manufacturing - An overview. Vaccine 35, 4064–4071 (2017).